扫描二维码

关注北京大学汇丰金融研究院官方微信/微博

Professor Harold James is the Claude and Lore Kelly Professor in European Studies at Princeton University and the official historian of the International Monetary Fund. In the interview with PKU Financial Review, Professor James states that, “technology and globalisation combine to provide powerful answers.”

PKU Financial Review: Today, the risk of debt expansion is a global problem. So do you think we should be as worried about the expansion of debt issue as we are about climate or aging problem?

Harold James: Debt is absolutely one of the central issues that I think concerns policy makers and increasingly also voters and citizens in rich countries as well as in emerging markets country.

So debt in poorer countries has been a big issue on the international agenda. And it's one of those to deal with it. We have to think of ways of dealing with it. But what I think is new is the expansion of large public debt in some of the rich industrial countries and the extent of the debt it is such that you can make predictions about how much more of national income would have to be spent on debt service and how costly that will be inhabit will constrain other choices that if you're paying so much on debt service, you can't pay so much on social security, you can't put that much into investment, you can't put that much into security.

And this is the world that is also one that the United States is going to live in. I think it was predictable: whoever had won the November election, just now in the United States, whoever the next president who would have been, they would have had to have dealt with a very, very substantial debt problem. That's even clearer, I think in a situation where Donald Trump has promised a lot of tax cuts and so the tax cuts of our going to increase the size of the deficit and they rise very acutely at the issue of how that debt is funded.

Some rich countries, I think look back on one particular experience in September, October, 2022 very, very briefly. The UK government had a tax reduction program that would have led to a tax cut of about £45 billion. It's not an enormous amount, maybe 2% of GDP. So on the face of it, you shouldn't have thought that it was that destabilizing, but it set off a really tremendous panic reaction on the markets. And that kind of panic reaction is one that I think is going to hang over the world and it's also a possibility and question mark that would hang over the next US administration.

PKU Financial Review: Today, even top economies, such as G20 face many challenges, such as political polarization, excessive debt burdens, unsustainable welfare policies and geopolitical conflicts. Based on your observations, do you think it is a better era or worse era for developing countries?

Harold James: It's undoubtedly a better era for developing countries. I think also that is something where the view of the world looks very different depending on where you are. If you're in the mature industrial economies, there's some feeling of skepticism or some feeling that globalization hasn't been very good for many groups in those societies. But if you go to, for instance, if you go to Brazil or you go to Mexico, you go to big emerging market economies. But also if you go to smaller places, if you go to Vietnam, if you go to Armenia, these are countries that have been big beneficiaries of the opening up of globalization.

And in general, the globalization effect has been one of taking a lot of people all over the world out of poverty. And you've seen that in Asia. You've seen this in Latin America, you're beginning to see it in Africa. And this is enormously important because the poverty and the hunger and poor living standards and vulnerability to disease were the characteristics of a lot of the world in the 20th century. And one of the big successes is really of the period of substantial globalization since the late 20th century has been to see a widespread diminution upon this eradication of poverty, but a radical diminution of poverty.

And that's I think why the future of the world is really dependent on these countries, poorer countries, the countries that we call emerging kids, who will see that they have a responsibility also for continuing the globalization story because it's simply been such a big success story. That is obviously very, very important to China.

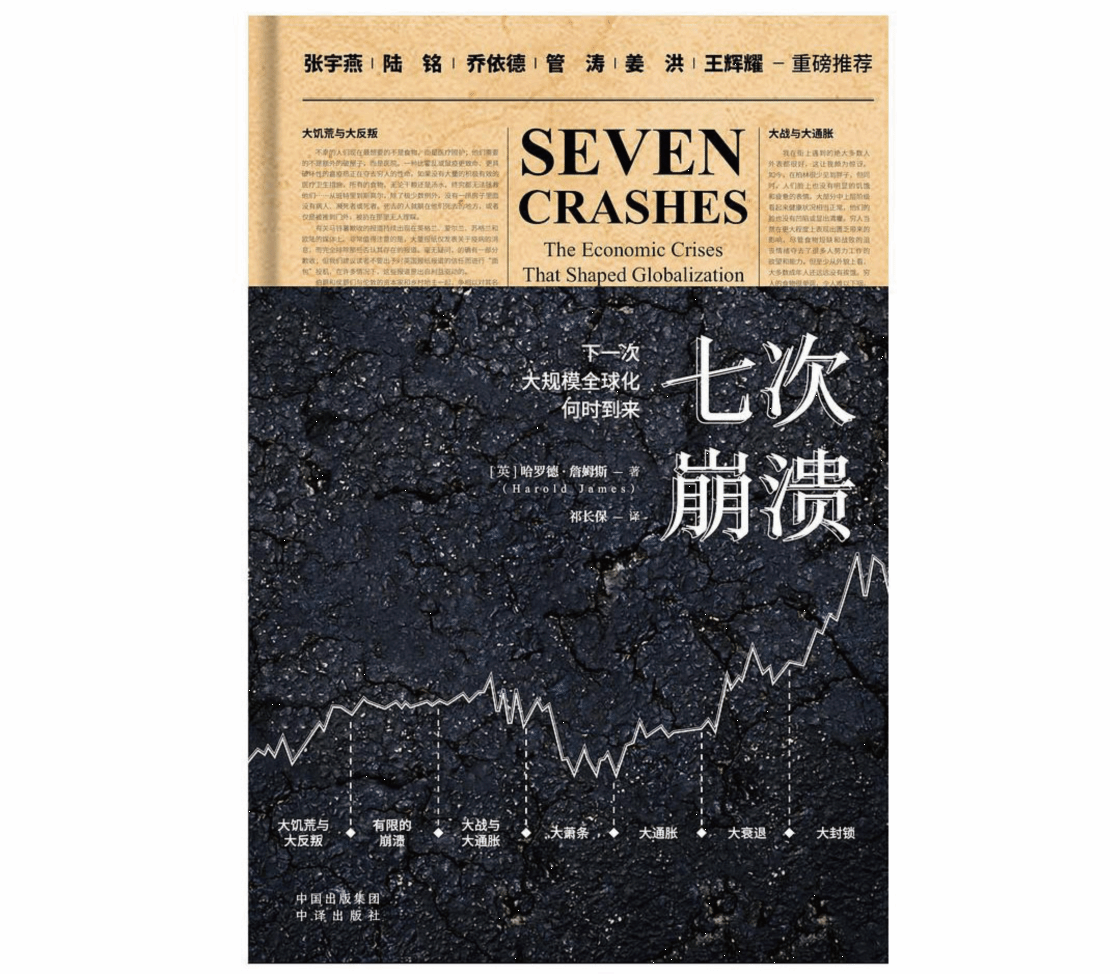

PKU Financial Review: In your book "Seven Crashes", you point out that "the lesson of history is that a crisis of some kind of globalization leads to a higher degree of globalization." Many believe that "globalisation is dead". What do you think is the new impetus for the eventual "rebirth" of globalization?

Harold James: I'm relatively optimistic about the future of globalization, at a time when many people are very skeptical and worried that the big industrial countries, in particular are turning against globalization. So it seemed to me that this was an important moment to think about the way in which globalization had developed in the past and where the turning points were, what prompted more globalization and what prompted a push back against globalization.

So it seemed to me that there were historical examples and I deal with one in the middle of the 19th century and one in the 1970s. When a supply shock and negative supply shock, the scarcity of something, the scarcity of food in the 19th century or the scarcity of energy in the1970s led it first to a kind of policy confusion into a lot of debate, into also a lot of skepticism about whether societies were going.

But in the end, after this confusion, what they did was to see that the fact of the scarcity really required them to trade with more countries and to open up their trading systems and that's what happened then in the 1970s, but also in the middle of the 19th Century. And I think basically story of the last years or so, since the outbreak of the pandemic, since the Covid crisis has been a period is characterized by more and more supply shocks, negative supply shocks. We're still in a world of scarcity.

The smaller the country is, the more they want to see trade, but even big countries realize that they can't be so sufficient. And so we're still very dependent on the rest of the world and we're dependent on Chinese products. If we were to have a really serious trade war, and obviously, that's one of the possibilities that's coming up with the new presidency with Donald Trump. But if we had a serious trade war, people would really quickly realize what they're missing, how basic goods are becoming more expensive, but how they're also becoming unavailable.

A lot of generic pharmaceuticals we import from India. But the components that are used the chemicals that are used to make these generic pharmaceuticals come from China. When people in the United States will be suffering from diseases that they can't treat properly because they don't get the antibiotics. There will be a big turning away into thinking that this is something that was in inappropriate policy.

So you learn the lesson of the book in general, is the supply shocks, negative supply shocks in the end push more globalization, and we're going to be dependent and continue to be dependent on goods and also more and more on services that are produced across the world.

PKU Financial Review: A more important issue than the choice between "for globalisation" and "against globalisation" seems to be whether we have managed globalisation properly and to what extent we have co-operated to support its smooth functioning. You have spoken of the need to build and manage a "resilient global financial safety net." So how close do you think we're to such a safety net, nowadays?

Harold James: I think it mixed records on how we've dealt with globalization because in a sense, they the characteristic of the old globalization of the early 21st century was about trade, trade in manufactured goods. The institution that supervises the rules for that was WTO.

The WTO was in a way born out of the wound of the 1990s after the Soviet Union collapsed, this trade was expanding. The old system of negotiating trade agreements under the gaps under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade with was a patchwork solution. The WTO was meant to replace it and it had a set of rules to an arbitration procedure. And in a sense, governments could rely on them. I thought it was very striking in the early 2000s. The George W. Bush administration in the United States wanted to do some steel tariffs. And they did that, but they knew that would be appealed to the WTO and they knew that the WTO would tell them that they can't do that. And so they did pull it back. It was helpful, I think, for governments to have this system.

Since 2008,the WTO has been more and more stalled. In the first Trump administration, the United States stopped appointing people to the arbitration panels. And this system doesn't work anymore. And should we be that worried about it? In a sense, I don't worry so much about it because I also think that the character of globalization is shifting. We're shifting more and more to a world in which the important sector is more and more in services and less in goods. I think actually measure this in a quite interesting way, that since the 2010s, the volume of traded goods compared to world GDP is been stagnating or even falling slightly, but the volume of traded goods relative to world manufactured output has remained more or less steady. It's that we're actually consuming less in the way of goods.

That's not surprising because we're in a more mature economy is a whole in the world, but what we are trading is more and more in services and that will continue and it has continued all the time through the Covid period, through the geopolitical escalations.

And we're going to find that we trade more for instance, in educational products, in legal services, in something like book preparation. But I think above all in medical services. And these are things that don't depend on anything being shipped and in a sense, live in a different world of rules than the world that the WTO administers in that sense. Maybe it's not a tragedy that the WTO has lost capacity to act, but we're going to imagine new ways in which this world of traded services holds us together and makes us more prosperous.

PKU Financial Review: You mentioned that the character of globalization has changed from trading goods to trading services, and technology is an important part. It is the key to shaping the future of globalization. But we have also noticed that the emergence of industrial robots will reduce workers, wages and make them more vulnerable to unemployment, resulting in greater inequality of social wealth. Research by Angus Deaton has shown that inequality poses a risk of democratic disintegration. So combined with the recent US election, do you think technology shocks will amplify political risk in the future?

Harold James: I'm glad you made that point because the technology in globalization of acted really together as two forces that worked in the same direction.

The results of the combination of the increased trade and the technical changes were indeed this story of the loss of manufacturing jobs. But I think maybe this is the historian speaking when I think of a very long term perspective, this is exactly like the story of people in pre modern societies who used to work mostly in agriculture. So most of the population worked in producing the food needed to supply everybody and the rest of the population that non-agricultural population was relatively small. And then agriculture became more efficient. You learned how to apply fertilizer and you learned how to do mechanization. The first of all, in the UK already in the 19th century, only a very small proportion of the UK's population worked in agriculture by the end of the 19th century. For the other European countries, it took longer to get there, but they're there now, it's a relatively small proportion of the population that works in agriculture.

Your point about robots is exactly correct. That's in the 21st century when we were worried about foreign imports and we were worried about the competition of produces elsewhere in the emerging markets in China. And one of the moves that many companies did it was to re import production back home or it is so called onshoring of jobs. But it was really an onshoring of production rather than jobs because the production was mostly done by robots. If you look at a modern automobile factory, you will see very few people are actually on the factory floor, just in particular processes they're doing the work.

And so the long term story is that the number of people working in industrial jobs will continue to decline and people who find new jobs and that's always been the story of these big changes. The people who worked in the new jobs will be doing new things and will be employing more people in, for instance, education and health care and care for the elderly. And there's an enormous possibility of expanded employment there. And the most interesting thing about that and there have been some really nice empirical studies of this is what the effect of the automation there is on incomes and the rewards that go to different skill levels. And there have been some studies of this, for instance, in the healthcare sector. And the finding is that the application of AI in health care enables the lowest skilled workers to improve their productivity most.

So the gains that come from AI revolution will be to low skilled workers and often also to people who have a kind of human skill or empathy or ability to deal with other people that you can't supply by machine.

And so the interaction between the human AI facilities will be both income increasing, income enhancing. And we're actually increasing the value of the product that they're giving whether it's health care or care for the elderly or I think you will find the same in the education that's in the past, you depended really on going to a good school with a very good teacher. In some ways AI can duplicate a lot of that, but you still need somebody to Guide you through the AI and that will be a process which is open to, I think a large number of people, they don't need to know what's in the inside of the AI is it where they don't need to be able to do that, but they do need to have the ability to deal with human beings.

And so in that sense, that again is another reason, at least for me to be optimistic about this process that so where in the world is changing very rapidly. But It's not a question of the gains of this revolution just coming to a small minority of people. If that were the case, I think we would in a situation which would be very unpleasant and also dangerous, socially dangerous, politically dangerous, morally.